Section 7.3

Status of Lichen

Common Powderhorn (Cladonia coniocraea)

91.0% intact on average

The status of 33 lichens associated with old deciduous and mixedwood habitat in the Al-Pac FMA area is, on average, 91.0% as measured by the Biodiversity Intactness Index.

This means most of the habitat for lichen species is in good condition, but habitat suitability is lower in some areas due to human development activities.

Introduction

Introduction

Intactness and sector effects are summarized for lichen species associated with old deciduous and mixedwood forests in the Al-Pac FMA area and AEI.

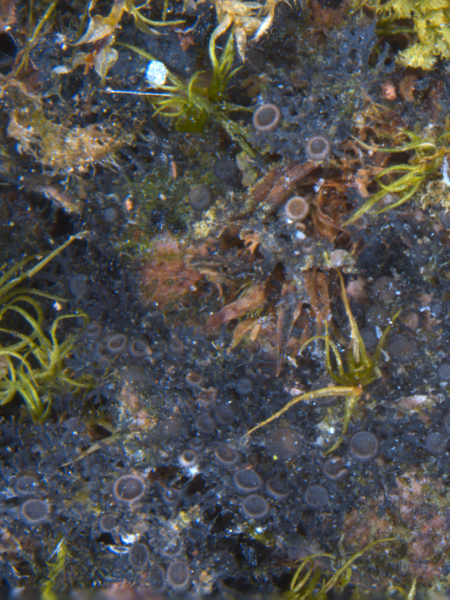

Concentric Pelt (Peltigera elisabethae)

Photo: Diane Haughland

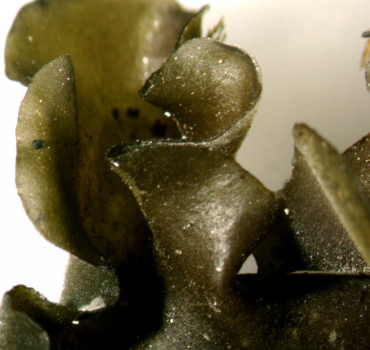

Appressed Vinyl Group(Leptogium subtile)

Photo: Diane Haughland

Principle 8: Monitoring and Assessment

Criterion 8.2 – Monitoring and evaluating environmental and social impacts of activities carried out in the management unit

FSC Indicator 8.2.3 (3) is supported by providing up-to-date ‘best available information’ on the status of naturally occurring native species from six taxa that can inform on the effectiveness of conservation and restoration actions taken within the FMA over time (linked to FSC Criterion 6.6).

Results

Results

Intactness of 33 lichen species associated with old deciduous and mixedwood forests was found to be, on average:

Highlights

- Out of the 33 lichen species associated with old deciduous and mixedwood forests in the Al-Pac FMA area, intactness was > 90% for 18 species and between 80% and 90% for 14 species. The two species that deviated the most from intactness reference conditions were Blister Paw (Nephroma resupinatum) at 78.2% and Bearded Jellyskin Lichen (Leptogium saturninum grp.) at 78.3%.

- Habitat suitability for all but three old forest lichen species is predicted to have declined between 2010 and 2016 as indicated by the drop in intactness over this time frame, from 92.3% to 91.0%.

- Intactness dropped by at least 2 percentage points for eight species with the Appressed Vinyl Group (Leptogium subtile grp; 93.0% in 2010 to 84.9% in 2016) and Peppered Pelt (Peltigera evansiana; 93.2% in 2010 to 85.7% in 2016) showing the largest reductions.

- Old-forest lichens are disproportionately affected by human footprint because, as of 2017, 54% of human footprint had occurred in deciduous and mixedwood forest, compared to other vegetation types.

- Intactness of old forest lichens was higher in the Al-Pac FMA area than in the AEI; this can mainly be attributed to the presence of agriculture footprint and energy footprint associated with the surface mineable area in the AEI, which removes their preferred old-forest habitat.

Bearded Jellyskin Lichen (Leptogium saturninum grp.)

Photo: Diane Haughland

Diane Haughland

Diane Haughland

Hammered Shield Lichen (Parmelia sulcata)

Photo: Diane Haughland

Lustrous Beard (Usnea glabrata)

Photo: Diane Haughland

These results have benefited from collaboration between the ABMI and various partners and contributors. More details are available in Collaborators and Contributors.

Sector Effects

Sector Effects

Local-footprint Sector Effects

To understand which industrial sectors are most impacting lichen species associated with old deciduous-mixedwood forests in the Al-Pac FMA area, the local-footprint figures show how species' relative abundance is predicted to change within each footprint compared to the habitat it replaced (Figure: Local-footprint Sector Effects).

- With few exceptions, all sectors decrease habitat suitability for lichen species associated with old deciduous/mixedwood forests in the Al-Pac FMA area because these activities impact their preferred habitat.

- Within forestry footprint, the populations of all old forest lichen species but one— Lilliput Vinyl (Leptogium tenuissimum)—are predicted to be less abundant than expected compared to in the habitat it replaces, with 20 species predicted to be at least 50% less abundant in forestry footprint.

Sector Effects on Regional Lichen Populations

The regional population figures show the predicted change in the total relative abundance of old forest lichen species across the Al-Pac FMA area due to each sector’s footprint (Figure: Regional Sector Effects).

- Regional effects are much less than local-footprint effects because a great deal of old forest lichen habitat has not been disturbed by human footprint in the Al-Pac FMA area.

- For transportation, energy and urban/industrial footprint, regional population effects of industrial sectors on lichens associated with old deciduous forest were small—between -1.8% and +7.2%.

- Forestry footprint resulted in the largest predicted changes to suitable habitat for many old forest lichens—on average -7.4%—because harvesting is the largest footprint type in the FMA area. Twelve species are predicted to decrease by at least 10% at the regional scale as a result of forestry footprint.

To view species-specific sector effects, use the drop-down menu to select a species of interest.

References

Boudreault, C. P. Drapeau, M. Bouchard, M-H. St-Laurent, L. Imbeau, and Y. Bergeron. 2015. Contrasting responses of epiphytic and terricolous lichens to variations in forest characteristics in northern boreal ecosystems. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 45:595-606. dx.doi.org/10.1139/cjfr-2013-0529.

Ellis, C.J. 2012. Lichen epiphyte diversity: a species, community and trait-based review. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 14 (2012):131-152.

Least Powderhorn (Cladonia norvegica)

Photo: Diane Haughland