Section 5.2

Species Spotlight: Woodland Caribou

Featured Projects: Landscape Disturbance, Climate Change & Impacts on the Woodland CaribouA collaboration of Al-Pac, RICC and the ABMI's Caribou Monitoring Unit

Boreal Woodland Caribou is federally and provincially listed as Threatened due to recent population declines.

Al-Pac, as part of the Regional Industry Caribou Collaboration (RICC), is working with the ABMI’s Caribou Monitoring Unit (CMU) on four projects assessing the impacts of natural disturbance, landscape disturbance, and climate change on caribou populations in and around the FMA area.

Photo: Rob Serrouya

_Rangifer%20tarandus-web-2.jpg)

Photo: Nancy S

Photo: Rob Serrouya

Woodland Caribou Research

Introduction

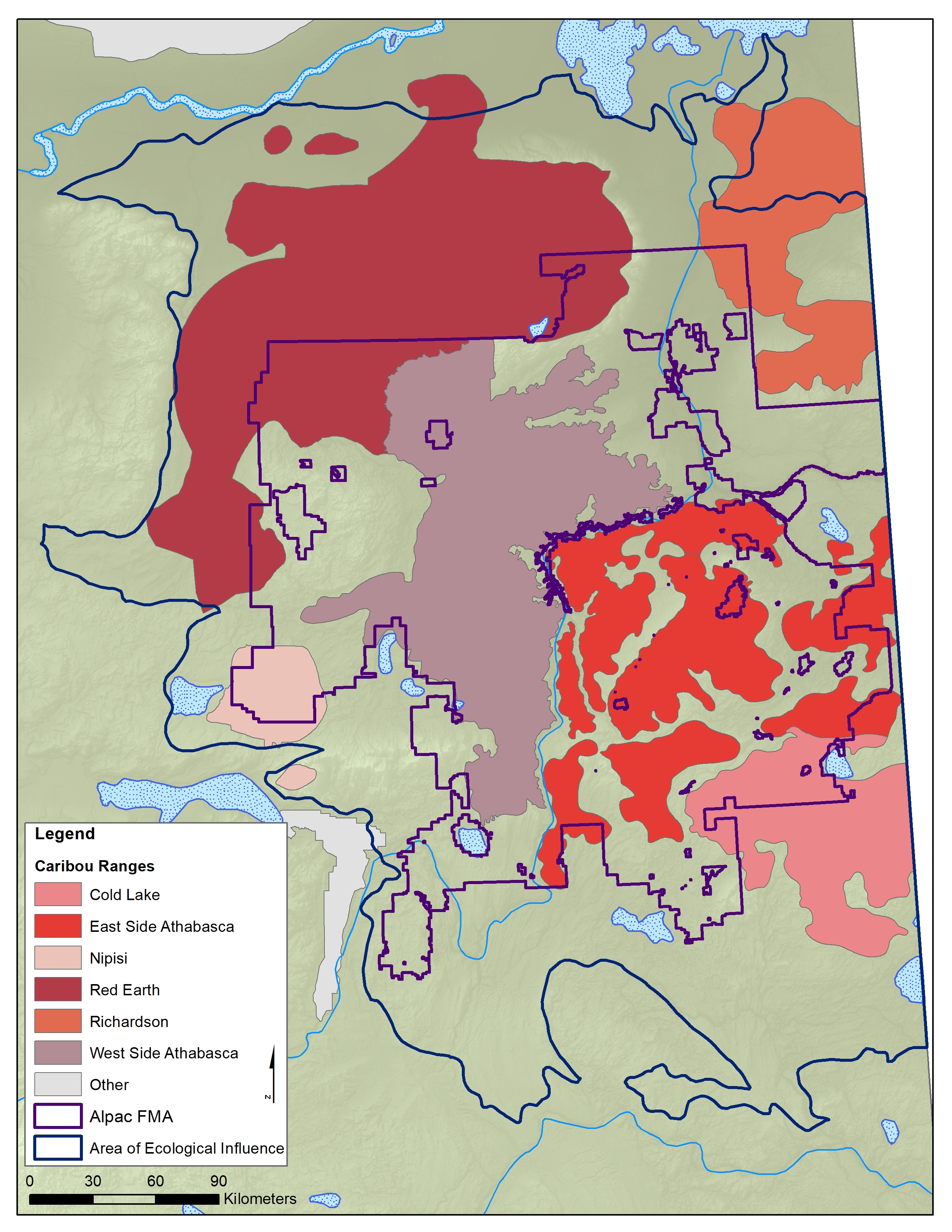

Populations of boreal Woodland Caribou are declining throughout much of their distribution, including in the six ranges that completely or partially overlap with the Al-Pac FMA (Figure: Woodland Caribou Range Map). This species is federally[1] and provincially[2] listed as Threatened because of these declines. Landscape disturbance and climate change are implicated in Woodland Caribou declines because:

- Landscape disturbance—both natural (e.g., fire) and human-caused (e.g., forest harvesting)—results in the creation of younger forests, which increases the number of prey species other than Woodland Caribou, mainly Moose and Deer[3,4,5].

- Human footprint features, such as roads, pipelines, and seismic lines allow wolves to move "faster and farther", increasing their hunting efficiency[6]. These linear features serve as access routes for wolves into previously inaccessible Woodland Caribou habitat[7].

- Climate change has resulted in milder winters, which favour the northward expansion of White-tailed Deer[8] into caribou ranges.

Ultimately, these factors, alone or in combination, result in larger populations of Moose and Deer in Woodland Caribou range; higher prey densities support increased numbers of predators, which leads to higher caribou predation. While the links between caribou population decline and these factors are well-established, the relative importance of each factor on caribou populations is largely unknown. This knowledge is critical for developing effective and cost-efficient strategies for conserving caribou.

Therefore, Al-Pac, as part of its involvement in the Regional Industry Caribou Collaboration (RICC), is working with the ABMI’s Caribou Monitoring Unit (CMU) on four projects assessing the relative importance of natural disturbance, human footprint, and climate change in terms of their impact on caribou populations. These projects are described below; more details on the CMU are available in Collaborators and Contributors.

Figure: Woodland Caribou Range Map. Summary of Woodland Caribou ranges that overlap the Al-Pac FMA area.

Principle 6: Environmental Values and Impacts

Criterion 6.4 – Protection of rare and threatened species and their habitats

CMU research supports caribou management requirements outlined in FSC Indicator 6.4.5b by increasing understanding of the effects of land management and natural disturbances on caribou-predator-prey-landscape ecology.

Landscape Disturbance: Understanding Fire Effects on Caribou Demography

Project funded by: RICC

For complete results see: DeMars et al. 2019. Moose, caribou, and fire: have we got it right yet? Canadian Journal of Zoology: 97:866-879. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjz-2018-0319.

Purpose: Evaluate the response of moose populations to fire in areas of the boreal forest that overlap Woodland Caribou range.

Background: Fire increases the amount of early successional habitat in the boreal forest, which is thought to improve habitat suitability for moose. If moose populations increase post-fire, caribou may be negatively impacted because as moose populations rise, predators such as wolves are expected to increase as well.

Key Findings: Moose either avoided or showed little use of burns less than 25 years old. Moose also did not increase in density in burns less than 40 years old.

Management Implications: Because caribou management is primarily focused on minimizing disturbance impacts in caribou range, moose showing minimal response to burns has important management implications. These results suggest that moose-mediated impacts of disturbance on caribou populations may vary by disturbance type (e.g., fire vs. harvest areas) and by geographic region.

Photo: ABMI

Photo: ABMI

Landscape Disturbance: Understanding Human Footprint Impacts on Caribou Mediated by Changes to the Large Mammal Community

Project funded by: Canada’s Oil Sands Innovation Alliance (COSIA)

Purpose: Assess the degree to which human footprint may be influencing predator and prey population densities by potentially improving regional habitat quality for black bears and white-tailed deer species.

Background: Human land-use increases the availability of young forest, potentially increasing the available food for moose, deer, and black bears, which consequently increases the density of caribou predators (e.g. wolves and bears).

Preliminary Findings: Cumulative human footprint under current conditions improves regional habitat quality for black bears and white-tailed deer by ~6%. Seismic lines alone accounted for 1% and 2% improvement in habitat quality for bears and deer, respectively.

Management Implications: These preliminary results suggest that human footprint likely does not substantially influence deer and bear habitat quality, though human footprint may operate by alternative mechanisms to increase predation risk to caribou.

Research in Progress

Landscape Disturbance and Climate Change: Using Remote Cameras to Assess the Relative Importance of Climate Change and Human Footprint on the Northward Expansion of White-tailed Deer

Project funded by: RICC

Project summary: Within western Canada, milder winters and landscape alteration by natural resource extraction are both thought to facilitate the expansion of white-tailed deer populations, which are invasive to northern boreal Canada[8]. Expanding white-tailed deer populations may negatively impact Woodland Caribou by supporting high predator populations and, potentially, by the transmission of novel diseases[9,10].

Remote camera traps have been deployed in a study design that leverages differences in human footprint (Alberta has 3.6 times more disturbance than Saskatchewan) within similar climatic regions to disentangle the effects of climate and human footprint on deer relative abundance.

Project initiated: 2017

Project completion: ongoing

Photo: ABMI

Photo: Hans Mohr

Landscape Disturbance and Climate Change: Assessing the Relative Importance of Climate Change and Human Footprint to Caribou Conservation in the Alberta Oil Sands Region

Project funded by: COSIA and RICC

Project summary: This research is a “state-of-knowledge” synthesis of evidence aimed at disentangling the effects of climate change and human footprint on Woodland Caribou. This research examines wolf use of linear features, landscape disturbance increasing habitat suitability for ungulates, and how a changing climate may increase deer populations. Results for this research will be used to identify caribou management strategies that have the greatest chances of success. For example:

- if climate change is the main driver of deer expansion, then habitat restoration will be expected to have less benefit for caribou;

- if habitat is improved for moose and deer as a result of human footprint, then habitat restoration is expected to have greater benefits for caribou populations.

Project initiated: 2019

Project completion: December 2020

References

COSEWIC. 2002. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the woodland caribou Rangifer tarandus caribou in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xi + 98 pp.

Dzus, E. 2001. Status of the Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) in Alberta. Alberta Environment, Fisheries and Wildlife Mnanagement Division, and Alberta Conservation Association, Wildlife Statis Report No. 30, Edmonton, AB. 47 pp.

Seip, D.R. 1992. Factors limiting woodland caribou populations and their interrelationships with wolves and moose in southeastern British Columbia. Canadian Journal of Zoology 70:1494-1503.

James, A.R.C., S. Boutin, D.M. Hebert, and A.B. Rippin. 2004. Spatial separation of caribou from moose and its relation to predation by wolves. Journal of Wildlife Management 68:799-809.

Latham, A.D.M., M.C. Latham, N.A. McCutchen, and S. Boutin,. 2011. Invading white-tailed deer change wolf-caribou dynamics in northeastern Alberta. The Journal of Wildlife Management 75:204–212.

Dickie, M. R. Serrouya, R.S. McNay, and S. Boutin. 2017. Faster and farther: wolf movement on linear features and implications for hunting behaviour. Journal of Applied Ecology 54(1):253-263.

DeMars, C.A. and S. Boutin. 2018. Nowhere to hide: effects of linear features on predator-prey dynamics in a large mammal system. Journal of Animal Ecology 87(1):274-284.

Dawe, K.L., E.M. Bayne, and S. Boutin. 2014. Influence of climate and human land use on the distribution of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) in the western boreal forest. Canadian Journal of Zoology 92(4):353-363.

Hannaoui S, H.M. Schatzl, and S. Gilch. 2017. Chronic wasting disease: Emerging prions and their potential risk. PLoS Pathog 13(11): e1006619. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1006619.

Myseterud, S. and C.M. Rolandsen. 2018. A reindeer cull to prevent chronic wasting disease in Europe. Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2: 1343-1345. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0616-1.

Photo: Rob Serrouya